In 2011 Philip Roth was awarded the Man Booker International

Prize for lifetime achievement. In the lead-up to an intimate celebratory

dinner that he was due to attend with Roth in New York, Rick Gekoski, chairman

of the judges, asked around to see if there was anything he shouldn’t raise in

conversation with the thin-skinned and easily irritated novelist. The answer

was the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The Nobel has become for Roth, who turns 80 on March 19,

what the second world war was for Basil Fawlty: the great unmentionable. No one

who knows him would doubt that this brilliant, proud, ultra-competitive and

astoundingly self-absorbed writer wants to win the prize that no American

novelist has won since Toni Morrison in 1993, and which his friend and mentor

Saul Bellow won, at the age of 61, in 1976.

In a BBC interview in 2007, Roth, who lives alone in rural

Connecticut but also keeps a flat in Manhattan, loftily dismissed prizes as

“childish”. And yet the biographical note on every book he has published over

recent years is little more than an inventory of prizes: “In 1997 Philip Roth

won the Pulitzer Prize for American Pastoral. In 1998 he received the National

Medal of Arts at the White House ... ” He has won everything worth winning, it

seems, except the Big One, about which he must not be asked.

Philip Roth was born in Newark, New Jersey, the second son

of a lower-middle-class Jewish family. He attended Bucknell and Chicago

universities. As a writer, he first came to prominence in the early 1960s, a

time of heightened ambition and profile for the American novel. His early

influences included Joseph Conrad, Henry James, Bernard Malamud, Isaac Bashevis

Singer and, of course, Bellow, who had found a new way of writing about the

tumultuous challenges of American modernity in a voice uniquely his own. For

Roth, as for the likes of Bellow and Norman Mailer, writing was a kind of

heroic activity, an art of public engagement and performance.

“When success happens to an English writer,” Martin Amis

wrote in the early 1980s in an essay on Kurt Vonnegut, “he acquires a new

typewriter. When success happens to an American writer, he acquires a new

life.”

Roth’s life changed, irreversibly, with the publication of

his third novel Portnoy’s Complaint (1969). Wildly comic and wilfully

outrageous, it made him famous and it made him rich. It also made him many

enemies, especially in Jewish America – he was accused of self-hatred – and

among social conservatives, who were appalled by the novel’s sexual

explicitness and indecency (Portnoy is a furious masturbator), by its exuberant

excesses and irreverence. This, after all, was the late 1960s and Roth was a

man of his times, thrilled by the possibilities opening up around him.

Alexander Portnoy is a clever, disturbed young fellow and

he’s sickened by his own American reality. He is in open revolt against the

conventions and expectations of his petit bourgeois Jewish family. His mother

swaddles him in love and he dislikes his father. What shocked readers most

about Portnoy, Roth said in 2005, was not the sex, but “the revelation of brutality

– brutality of feeling, brutality of attitude, brutality of anger. ‘You say all

this takes place in a Jewish family?’ That’s what was shocking.”

Portnoy was the precursor to and archetype of all the Roth

men who were to follow, from Nathan Zuckerman, Roth’s fictional alter-ego, and

David Kepesh to Mickey Sabbath, the anti-hero of Sabbath’s Theater (1995),

which is generally considered to be one of his three best novels. (The others

are 1986’s The Counterlife and 1997’s American Pastoral.)

Roth Man, as Amis once called him, is sex-obsessed,

narcissistic, garrulous, often raging. He knows no bounds. He is wary of

commitment. He relentlessly asserts his individuality. But he is also isolated

and often deeply, hilariously confused – many of Roth’s novels are existential

comedies of misunderstanding.

In The Ghost Writer (1979), the first of the Zuckerman

novels, Nathan is staying at the house of his literary hero, an aged and

reclusive writer named EI Lonoff. An attractive young literary groupie is also staying

in the house. Zuckerman convinces himself that she’s having an affair with the

married Lonoff and, absurdly, that she is none other than Anne Frank. Roth Man

understands, indeed insists, that in our singularity and isolation we are

mysteries ultimately even to ourselves, and that life can be a kind of black

farce – Kepesh, in the late novella The Dying Animal (2001), speaks of the

“stupidity of being oneself”, of the “unavoidable comedy of being anyone at

all”.

To Roth, for whom sex and death are inextricably linked,

women can seem unknowable. There is very little romantic love in his fiction.

He writes very well about the love between a parent and a child – especially in

Patrimony (1991), American Pastoral and Indignation (2008) – or between siblings,

but seldom, if ever, between a man and a woman, a husband and a wife. For Roth,

marriage is a kind of cage in which couples are locked in mutual recrimination

and loathing.

“Did Roth hate women?” asks the Russian-American novelist

Keith Gessen, as part of a caucus organised by New York magazine to mark the

author’s 80th birthday. He suggests that a man who spends so much of his time

thinking about having sex with women cannot possibly hate them: misogyny is the

accusation most often and most damagingly made against Roth. “Still,” Gessen

continues, “it might be said that Roth is slightly less useful in a world that

is slightly more equal than the world he knew; where men and women do not stand

on opposite sides of the question of sex but arranged, together, sometimes

helplessly, against it; where sex is less of a battlefield and more of a

tragedy.”

Roth has been married twice and has no children. His second

marriage, to the English actress Claire Bloom, ended notably unhappily. Roth

fictionalised aspects of his life with Bloom and this wounded her. In 1996, she

published a memoir, Leaving a Doll’s House, in which she denounced her former

husband, accusing him of misogyny and adultery. She wrote of his “deep and

irrepressible rage: anger at being trapped in marriage; fear of giving up

autonomy; and a profound distrust of the sexual power of women”.

Roth himself has said: “Making fake biography, false

history, concocting a half-imaginary existence out of the actual drama of my

life is my life.” He is fascinated by doubleness and deception, hence all those

metafictional tricks he plays and the alter-egos through whom he speaks. They

invariably share much of his own early biography – the Newark boyhood, the

conflicted Jewish identity, the troubles with women – as well as his

preferences and prejudices. Several of his novels feature characters named

Philip Roth – the best of them being Operation Shylock (1993), set partly in

Israel and exploring the period when Roth was recovering from depression and a

breakdown after heart surgery. He simultaneously asserts the veracity of the

stories he tells while seeking to undermine them by drawing attention to their

artificiality. Roth’s strategy is one of complete disclosure interwoven with

complete disavowal. He’s only too happy to show the strings from which his

creations dangle.

In November last year, Roth declared that he would write no

more novels. “I’m done,” he said. Can it really be that this most prolific and

prodigiously gifted novelist, this writer who, after his divorce from Bloom and

retreat to rural Connecticut, began publishing a series of masterpieces in his

sixties and seventies, will write no more? There has, I think, been nothing

comparable to his late flourishing in the history of Anglo-American letters. It

is difficult to accept that this has now come to an end, when as recently as

2010 Roth published one of his most poignant and tender novels, Nemesis, set

during a polio epidemic in wartime Newark. Many of the novels of Roth’s late

period are preoccupied with illness and death, as is Nemesis. The scabrous

comedy and laughter disappeared from his work around the time of Sabbath’s

Theater. The old rage was replaced by something approaching resignation. Even

Zuckerman withdrew from centre stage and became, in Roth’s great

political-historical trilogy comprising American Pastoral, I Married a

Communist (1998) and The Human Stain (2000), the narrator no longer of his own,

but of other people’s stories, a benign facilitator.

In Exit Ghost (2007), a belated follow-up to The Ghost

Writer, an ageing and sick Zuckerman (he now wears nappies because of

incontinence following prostate surgery) encounters a cocky, smart-talking

literary academic in Central Park. The young man is described, in a jewelled

phrase, as being “savage with health, and armed to the teeth with time”.

Philip Roth knows he is running out of time. He speaks now

of the end – certainly of the end of his writing life. He ought to have won the

Nobel Prize long ago, but perhaps his work is simply too American for the

august Swedes of the Nobel committee, who have grumbled about the parochialism

of the American novel, of how it looks inward rather than out to the rest of

the world. That is nonsense, of course. The greatest living American writers –

Cormac McCarthy, Don DeLillo and, preeminently, Roth – are universalists who in

radiant prose ask, again and again: what does it mean to be human and how

should we act in a world that is as mysterious as it is indifferent to our

fate?

At the end of The Tempest, as he prepares to take his leave,

Prospero, a magician of words, hints that “the story of my life” is ending, and

now “Every third thought shall be my grave”. Roth has told the story of his

life many times and in many different ways, and now he is done.

“At the end of his life,” Roth said in an interview last

year, “the boxer Joe Louis said, ‘I did the best I could with what I had.’ It’s

exactly what I would say of my work: I did the best I could with what I had.”

We can ask no more.

Jason Cowley is editor of the New Statesman

__

De FINANCIAL TIMES, 16/03/2013

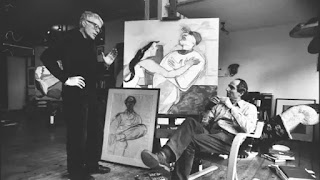

Imagen: Philip Roth (right) and RB Kitaj in 1985 with the artist’s

drawing of the author and a painting of a combative couple

No comments:

Post a Comment