ROLAND BOER

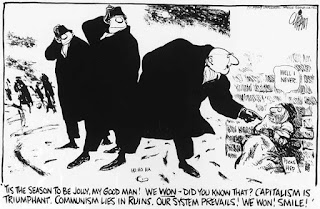

Communism has ‘failed’, or so the common observation goes.

More often, one hears the opinion that the Soviet Union ‘failed’, or that the

communist countries of Eastern Europe did so as well. But what does ‘failure’

mean here? Usually it simply means that they came to an end, even that they

were not eternal. Dig deeper and the ‘failure’ is marked by a host of items:

dictatorship and totalitarianism rather than ‘democracy’ and ‘freedom’; the sad

reality that was far from the perfect dream; the fragmentation that arose

instead of the voluntary union of working people from many ethnic and religious

backgrounds; state capitalism instead of communism; and simple betrayal of

revolutionary Marxism. My answer in the face of this persistent propaganda is

that they did not fail, and that communisms – plural – as such have not failed.

To be sure, they had and continue to have many problems, for they are not

perfect by any means, but this is not failure. In order to deal with the

various caricatures of failure, let us travel to various parts of the world,

both ‘post-communist’ and still communist.

Romanian ‘Dictatorship’

‘Post-communist’ is what the locals call Romania. Neither

communist nor capitalist in any conventional sense, it is in a period never

experienced before and thereby unique. One feature of this period is the coming

to terms with Nicolae Ceaușescu, the second communist leader of Romania, from

1967-1989. On one side, Ceaușescu is held up as the example of all that is bad

about communist dictatorship. Propagator of the ‘mini-cultural revolution’

after his ‘July Theses’ in 1968, he fostered a North Korean style personality

cult, gave himself many honours, attempted to build ‘socialism in one family’

by appointing family members to high posts, and destroyed the country

economically in the 1980s by attempting to repay onerous debts incurred from

Western European countries. In short, he was the most ‘Stalinist’ of all the

eastern bloc leaders, ruling by decree and through his feared secret police,

the Securitate. The lynching of him and his wife in 1989 is

regarded as unfortunate but necessary.

Yet, in a widely publicised opinion poll in July 2010 by

IRES (Romanian Institute for Evaluation and Strategy), 41% of the respondents

said they would have voted for Ceaușescu if he had been alive and run for the

position of president. Further, 63% said their lives were better during

communism, while only 23% stated that their lives were worse. And 68% stated

that communism was a good idea, but had been poorly applied. The facetious

response to such a result is that it merely reflects a tainted nostalgia for

communism. But Romanians are smarter than that. Let me put this in perspective:

the respondents were reflecting on the worst period under the communist

government in the 1980s. Earlier, Ceaușescu had fallen into the trap of taking

up heavy loans from Western Europe for the sake of economic expansion.

However, by 1982, the debt had become an onerous burden, so

he decided to repay it through exporting much of Romanian agricultural and

industrial production. This resulted in shortages of food, fuel, energy, and

medicines. Yet, it was precisely this period that the respondents said was

better than what they have now. Since 1989, the situation has become decidedly

worse. The economic devastation of the 1990s, the de-industrialisation of

Romania as Western European countries bought up the factories and promptly

closed them, and then the swathe cut through the country after the rolling economic

crisis of 2008 – all these have made the 1980s look like a relatively benign

period. I cannot help thinking of Lukács adage: ‘bad communism is better than

good capitalism’.

Bulgarian ‘Perfection’

Ask an older Bulgarian today what they remember most from

1989 and it is highly likely she will say, ‘It was a glorious feeling to know

that when you made a phone call, you didn’t have the feeling that someone else

was listening’.

But ask, ‘Is it better now?’

And the answer will be, ‘We prefer not to answer that’.

The answer is soon obvious. Travel on any road and you find

it potholed beyond belief. Walk any street and you run a serious risk of being

knocked on the head by a falling brick or crumbling façade. Ask anyone what

they do for a living and the answer will be evasive, since less than 25% of the

population is in formal employment. Or if you inquire after someone’s family,

chances are the children have moved internationally to find a new life and job.

Indeed, in a few years after 1989, two million people left Bulgaria, reducing

its population from nine to seven million.

What about communism? Was it perfect? Did it meet its own

high aspirations? Denigrators are of course keen to point out its failings,

stressing the gaps between the grand aims of the Bulgarian Communist Party,

which was the government from 1944 to 1989, and its failings. But communism is

by no means perfect. As Lenin and Mao pointed out repeatedly, winning a

revolution is the easy part; constructing socialism is far, far more difficult.

So, let us see what the Bulgarian communist government did

achieve, keeping in mind the difficulties and a modest sense of what was indeed

achievable. The communist government had three leaders, the revolutionary hero,

Georgi Dimitrov (1946-49) who died too young, Vulko Chervenkov (1949-54) and

the long-lived Todor Zhivkov (1954-89). Zhivkov may have had his limits, like

any leader, but his time was marked by political stability and a steady

increase in living standards. The reason: communist central economic planning.

Already in the late 1950s, real wages increased by 75 per

cent, returning people to pre-war levels, while collective farm workers were

the beneficiaries of the first agricultural welfare and pension scheme in

Europe. By the 1960s, agricultural incomes rose by 6.7 per cent per year and

industrial incomes rose by 4.9 per cent annually. Consumption of healthy foods

– fruit, vegetables and even meats – increased significantly, while doctors and

medical facilities became commonly available. As a result, fewer children died

and people lived longer. While 138.9 in 1,000 children under the age of one

died in 1939, by 1990 it was 14 in 1000. And those who survived could expect to

live longer: life expectancy rose to over 68 years for men and over 74 years

for women. Indeed, a reasonable number could expect to make a century: in the

late 1980s, 52 people were found over one hundred years of age per one million.

Meanwhile, Zhivkov exercised his ‘tyrannical’ rule. People

often made jokes about his dialect and proletarian manners. But did Zhivkov

have the perpetrators arrested and punished by the secret police? No, he

collected them for a good laugh now and then. He was usually known as ‘bai

Tosho’ (old uncle Tosho) or ‘Tato’, a dialectical term for

‘poppa’.

Yugoslavian ‘Disunity’

Balkanisation is perhaps the term that captures best the

image of Yugoslavia – or, rather, the ‘former’ Yugoslavia. Tito may have kept

the disparate peoples of that part of the world together for a while, due to

his personal charm and iron fist, but it was only a matter of time before it

would all fall apart. Deep-seated ethnic hatreds and religious animosity –

between Islam, Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism – would resurface eventually,

and of course they did with the Balkan War of the 1990s. Or so the official

narrative went from the members of the EU and the NATO alliance, which

deliberately sought to destabilise and break up yet another socialist country.

The NATO attacks on Yugoslavia ensured that they would succeed.

However, the real situation was quite different. Yugoslavia

is one of the best examples of what has been called ‘affirmative action’ in

relation to ethnicities, cultures and religions. Given the range of peoples and

regions in Yugoslavia, the constitution was explicitly designed as an

affirmative action constitution. The Socialist Federal republic of Yugoslavia

comprised six republics and two autonomous provinces that were part of the

socialist republic of Serbia. Given the great ethnic diversity of Yugoslavia,

the constitution and the framework of the laws sought to ensure that smaller

groups were not discriminated against by larger ones. The measures included

very strong anti-discrimination laws, with heavy penalties for vilification in

terms of ethnicity, language, and religion. Further, in provinces and regions,

local people were encouraged to take up government positions, and local

languages, cultures, social formations and education were fostered. At a

federal level, all republics and autonomous regions, no matter what the size,

had equal representation in the federal government. This entailed toning down

the dominance of the larger parts, so they didn’t lord it over the others.

Needless to say, this was a constant work in progress, but

the model for this approach was the first affirmative action state in human

history – the USSR. It may come as a surprise to some, but the chief

theoretician of what was called the ‘national question’ was Stalin. Coming from

Georgia – a part of the world with some of the most complex intersections of

multiple ethnicities – Stalin developed an increasingly complex approach to the

question of ethnic diversity. This approach may have been primarily theoretical

before the Russian Revolution, but it grew significantly in the practical

experience that followed the revolution. Through the civil war and then the

immense task of constructing a very different state (since the former state had

largely collapsed and threatened to leave nothing but anarchy in the vacuum),

Stalin built his arguments.

The principle was that each ethnic area and group should

have the right to self-determination and autonomy, especially in light of

centuries of tsarist repression by the ‘great Russian’ majority. Only on this

basis would a new, voluntary union arise: ‘Thus, from the

breakdown of the old imperialist unity, through independent

Soviet republics, the peoples of Russia are coming to a new,

voluntary and fraternal unity’.[1] In practice, of course, this was easier said

than done. After the revolution, the old ruling elites in the various border

regions immediately claimed the right to secession and autonomy. Stalin was

astute enough to see through the game and the policy became one of recognising

autonomy only when a workers and peasants soviet formed the government in each

area. Further, such autonomy involved a delicate play of central policies and

regional initiatives. Thus, the central government sought to foster local

languages, culture, literature, education, government and even religion to some

extent. In some cases, especially in the southern and eastern border regions,

this required a program of educating and training local leaders and

institutions, even to the point of creating written languages in oral cultures.

At the same time, local initiatives fed into the policies of the central

government, which then changed its policies in light of such input.

Already in 1918, Stalin made a crucial breakthrough. Due to

the sheer size and diversity of what was to become the USSR, Stalin saw that

his position on the national question also applied to anti-colonial movements

throughout the world. So he wrote that the October Revolution ‘has widened the

scope of the national question and converted it from the particular question of

combating national oppression in Europe into the general question of

emancipating the oppressed peoples, colonies and semi-colonies from

imperialism’.[2] If one supports the emancipation of ethnic minorities within

the USSR, then the same should apply to any colonised place on the globe. Over

the following years, this insight was developed into an international policy of

supporting anti-colonial struggles around the world.

The result was the 1924 constitution of the USSR, which was

the first affirmative action constitution in the world. The crucial paragraph

of the declaration reads:

The will of the peoples of the Soviet republics, who

recently assembled at their Congresses of Soviets and unanimously resolved to

form a “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,” is a reliable guarantee that this

Union is a voluntary association of peoples enjoying equal rights, that each

republic is guaranteed the right of freely seceding from the Union, that

admission to the Union is open to all Socialist Soviet Republics, whether now

existing or hereafter to arise, that the new union state will prove to be a worthy

crown to the foundation for the peaceful co-existence and fraternal

co-operation of the peoples that was laid in October 1917, and that it will

serve as a sure bulwark against world capitalism and as a new and decisive step

towards the union of the working people of all countries into a World Socialist

Soviet Republic.[3]

A major feature of the constitution was the detailing of

equal roles for both a Federal Soviet and a Soviet of Nationalities. Stalin’s

observations on the initial treaty and then constitution indicate a range of

economic, political and international factors, but he made it clear that the

initiative actually came from the border regions, especially Azerbaijan,

Armenia and Georgia, which were later joined by Ukraine and Belarus. Needless

to say, the constitution did not solve all of the problems immediately, for it

remained a work in progress. Determining the status of each republic and region

was complex and at times did not reflect that actual nature of the local

situation. So these matters were constantly debated and reformulated, leading

to two revisions of the constitution in 1936 (under Stalin’s initiative and

with emphasis on the theme of the ‘brotherhood of the nations’) and the

constitution of 1977 (under Brezhnev), but the essence remained the same. Thus,

the 1936 constitution included the clause: ‘Any direct or indirect restriction

of the rights of, or, conversely, any establishment of direct or indirect

privileges for, citizens on account of their race or nationality, as well as

any advocacy of racial or national exclusiveness or hatred and contempt, is

punishable by law’.[4] Article 36 of the 1977 constitution contains the most

complete statement of this position:

Citizens of the USSR of different races and nationalities

have equal rights.

Exercise of these rights is ensured by a policy of

all-round development and drawing together of all the nations and nationalities

of the USSR, by educating citizens in the spirit of Soviet patriotism and

socialist internationalism, and by the possibility to use their native language

and the languages of other peoples in the USSR.

Any direct or indirect limitation of the rights of

citizens or establishment of direct or indirect privileges on grounds of race

or nationality, and any advocacy of racial or national exclusiveness,

hostility, or contempt, are punishable by law.[5]

This socialist model of state organisation carries through

today in China, where the ethnic minorities – more than 55 of them – are

fostered in similar terms, while efforts are made to keep in check Han

dominance.

Chinese ‘Capitalism’

‘China is more capitalist than any other country’– or so one

hears on a reasonably regular basis, even from socialists who perhaps should

know better. Old Maoists like Alain Badiou hold that China veered that way

under Deng Xiaoping, ‘he who follows the capitalist path’. Ephemeral socialists

like Slavoj Žižek opine that Chinese capitalism is unbridled in a way unlike

that of the bourgeois democracies of Europe. ‘State capitalism’ it is often

called, even more than the Soviet Union (the term ‘state capitalism’ was first

used by Karl Liebknecht to describe the German economy in the 1890s).

Various strands are responsible for such a characterisation

– anarchist criticisms, Trotskyite assessments, radical laissez faire assessments,

and time-bound Maoists – although all of them turn on an idealised, if not

romanticised, view of what communism should be. Such a view is idealist, since

it holds communism to be a rational idea that is yet to be realised, and

believes that communism is singular rather than plural. Needless to say, such a

communism always remains in the utopian future.

So let us attempt an analysis that takes into account the

realities of the situation in China today, rather than idealist projections of

a communism yet to come. In the tradition of Marx and Engels, I suggest three

variations on the socialist dialectic: the use of capitalism to build

socialism; the need to foster the full development of capitalism under

socialist guidance so that communism may emerge; the need for economic and

political strength in a global situation that remains hostile to Chinese

socialism.

The first may be drawn from Lenin’s justification of the New

Economic Program: using capitalism to build socialism.[6] For Lenin and the

soviet government it meant permitting certain levels of market exchange with

the countryside, granting concessions to some international mining companies

and industries, and employing specialists at higher rates of pay to rebuild an

economy and indeed country destroyed by a series of wars and revolutions.

In China and under Deng Xiaoping’s urging, the process began

to go much further, for Deng argued that there was no necessary contradiction

between socialism and some capitalist economic forms, assuming that the latter

would be directed by the former. Indeed, Deng Xiaoping understood the mandate

that Marxism is practice in the sense that it would make use of what would

unleash productive forces. The employment of some capitalist methods was to be

undertaken as a way of ‘accelerating the growth of the productive forces’.[7]

Deng always understood this approach as part of the strengthening of socialism,

not merely in terms of economic strength, but also in terms of political and

social strength. I would add that today this process continues, almost to the

point of paradox (to an outside observer). Thus, the 2014 meetings of the

Political Bureau of the Chinese Communist Party agreed to continue the process

of reforming the economy, while at the same time President Xi Jinping sought to

strengthen Marxism by blocking any push for bourgeois democracy, and by drawing

heavily on Mao Zedong concerning the ‘mass line’ campaign in its push for

closer integration and sensitivity between government and people.[8]

The second variation on the dialectic is to argue that the

full development of capitalism needs to be fostered under the direction of a

communist government that has already won power in a revolution. China is in a

unique situation, for it missed its chance to develop into a capitalist economy

and thereby develop the classic pattern for socialist revolution in the context

of a ‘mature’ capitalism. Instead, the socialist revolution happened before the

full development of capitalism. Thus, in order to develop its forces of

production to a point where they are superior to capitalist ones, China has

found it necessary to foster the economic potential of capitalist forces of

production so they may provide the basis of socialist forces of production.

That is, China has returned to a capitalist economy so as to

develop forces of production for socialism. This approach relies on an insight

from Marx: ‘A social formation never comes to an end before all the forces of

production which it can accommodate are developed, and new, higher relations of

production never come into place before the material conditions of their

existence have gestated in the womb of the old society’.[9] Socialism in an

orthodox sense is not socialism unless it develops from capitalism. Yet the

Chinese approach gives this Marxist orthodoxy an extraordinary and apparently

paradoxical twist, for China is already politically a socialist country. So it

has developed an approach in which the forces of capitalist production are

harnessed for the sake of creating a situation for the full realisation of

socialism. In this light we may read Mao Zedong’s observation, ‘Thus this

revolution actually serves the purpose of clearing a still wider path for the

development of socialism’.[10] This dialectic means that one is, in economic

terms, in favour of capitalism for the sake of the development of forces of

production, but that one is, in political terms, against capitalism for the

sake of the development of relations of production.

The third form of the dialectic is the most direct: the

drive for economic strength in whatever way is absolutely necessary, since

socialism needs to be powerful, economically and militarily, in order to

flourish. In China, this approach has borne obvious fruit. China has become the

second largest economy in the world and is disrupting the global status quo,

even without as yet realizing its full potential.[11] BRICS and the Shanghai

Cooperation Zone are already challenging the hegemony of the International

Monetary Fund and the World Bank. The increasing obsession with Chinese

economic power in the United States and Western Europe is but a reflection of

their own stumbles and declining position. Already in some respects, China is

more technologically advanced than any other place on the globe. And with

economic power comes military strength, which remains a necessity in the

Realpolitik of persistent hostility to socialism.

The ‘Betrayal’ of the Russian Revolution

The longest-lived effort to construct socialism was the

USSR, but in this case we find the deployment of one or both biblical

narratives – a ‘betrayal’ or a ‘Fall’ narrative – to account for its ‘failure’.

For many, Stalin embodies the manifestation of that betrayal. Was he not, after

all, a paranoid and omniscient dictator, ruling by a bloodthirsty and

capricious will? Caricatures aside,[12] once one opts for a narrative of the

‘Fall’, one is playing a theological game. By ‘Fall’ narrative I mean a

narrative that is structured in terms of a fall from grace, analogous to the

story in Genesis 2–3, in which Eve and then Adam eat of the

fruit of the forbidden tree (of the knowledge of good and evil) and are thereby

banished by God from paradise.

Since Stalin has been written off most as the quintessence

of the betrayal of Marxism – especially after the concerted efforts of

Khrushchev’s politically motivated ‘Secret Report’ and Hannah Arendt’s wayward

work, The Origins of Totalitarianism[13] – attention has turned to

Lenin. Did he too betray Marxism and the revolution, thereby setting up the

completion of that betrayal by Stalin? Did he begin the process of running the

revolution into the mud of authoritarianism, repression, and dictatorship?

Most feel that Lenin did at some point betray the

revolution, thereby setting the ‘Fall’ narrative on its way. The least generous

suggest that it happened even before the revolution, especially through Lenin’s

supposedly devious machinations and his refusal to cooperate with other

socialist groups such as the Mensheviks and

SRs, both

Left and Right wings.[14] Indeed, for such critics, communism by its very

nature leads to such betrayal. For others, the moment of the ‘Fall’ is the

October Revolution itself, or soon afterwards. The formulations vary, but the

point is the same: the party and even the working class disintegrate; the

Bolsheviks do everything possible to distort in most horrendous ways their own

principles; Lenin’s thought loses it coherence; bureaucracy becomes pervasive;

a transformation takes place from a flexible, democratic, and open party to one

of the most centralized and ‘authoritarian’ political organisations in modern

history; the dictatorship of the proletariat becomes the dictatorship of the

secretariat; the revolution shifts from being a revolution from below to one

from above; the democratic soviets crumble before a centralized and dictatorial

party.[15]

Unfortunately, such ‘Fall’ narratives bear an inescapably

theological dimension, in which a fall from grace obscures the complex

messiness of history. They also neglect Lenin’s repeated point that the

revolution itself is easy; far more complex is the construction of communism,

when many mistakes are made. Yet others lament the lost opportunities,

suggesting that a broad, cross-party socialist government, such as the one

established in the February Revolution, was the ideal.[16] Others entertain the

possibility that the brief time after the revolution was valid, but that the

‘civil’ war corroded all the gains, for it was a period of centralized control,

tough measures, the Cheka, and ‘war communism’, all of which betrayed

the revolution.[17] A solution for some is to side with Trotsky, arguing that

if he had won out over Stalin, the situation would have been far different.

Apart from the obvious fallacy of such a position, it succumbs to the dreams of

alternative histories.

All of them belong to the genre of revolutionary ‘Fall’

narratives, accounts of betrayal of the communist revolution. In response, I

rely upon the insight of Cockshott and Cottrell. Refusing the facile dismissals

by many on the Left in order to distance themselves from Stalin, they argue

that the full implementation of a communist economic system happened under

Stalin. Through the Five-Year plans beginning in the late 1920s, the capitalist

mode of extracting surplus value was replaced by a planned economy, in which

surplus was controlled and allocated by the planning mechanism.

Under Soviet planning, the division between the necessary

and surplus portions of the social product was the result of political

decisions. For the most part, goods and labour were physically allocated to

enterprises by the planning authorities, who would always ensure that the

enterprises had enough money to ‘pay for’ the real goods allocated to them. If

an enterprise made monetary ‘losses’, and therefore had to have its money

balances topped up with ‘subsidies’, that was no matter. On the other hand,

possession of money as such was no guarantee of being able to get hold of real

goods. By the same token, the resources going into production of consumer goods

were centrally allocated. Suppose the workers won higher ruble wages: by itself

this would achieve nothing, since the flow of production of consumer goods was

not responsive to the monetary amount of consumer spending. Higher wages would

simply mean higher prices or shortages in the shops. The rate of production of

a surplus was fixed when the planners allocated resources to investment in

heavy industry and to the production of consumer goods respectively.[18]

They do not shy away from the conclusion that this outcome

was largely what Marx anticipated, with one caveat: it took place under a form

of authoritarian communism. I would add that such a phase is necessary for any

effort to construct communism. Genuine revolutionary fervour characterized much

of the effort, but for those less inclined to engage, forced labour, exile, and

‘terror’ were deployed. Stalin embodied the sheer grit of the revolutionary

‘miracle’ required to adopt such a radically new economic system.

Conclusion

As Domenico Losurdo has pointed out, the demonization of

communism has continued unabated since the nineteenth century, so much so that

it has become a comprehensive black legend.[19] He also argues that it has

become a twisted caricature that has little to do with actual history. The same

may be said of the motif of communism’s ‘failure’ – in terms of dictatorship,

perfection, dissent, the turn to capitalism and betrayal or ‘Fall’ narratives.

But when pressed, a critic will fall back on the simple point that communism in

many places came to an end. The toppling of the Berlin Wall is the symbol and

the rolling back of communism in Eastern Europe and even in parts of Asia (such

as Mongolia) is the reality – or so it is argued. The reply is equally simple:

let us leave aside the continuing socialist countries in Asia, let alone the

South American versions of socialism, and ask: why is longevity, or indeed

eternity, a criterion for success? The fact that communism has actually

appeared over more than a century is ample proof of the success and continuing

appeal of communism. It may be for shorter or longer periods of time, it may

even establish itself relatively permanently, but it has appeared. I propose a

more modest criterion of success. If a socialist revolution is able to see off

the counter-revolution – in the form of internal opposition and international

hostility – then it is a success. The reason is that after crushing the

counter-revolution, the opportunity arises for the peaceful construction of

socialism in all its multiple forms. And if it comes to an end sooner than one

hopes, the old adage applies: try and try again.

End notes:

[1] J. V. Stalin, ‘The Government’s Policy on the National

Question,’Works, volume 4 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1953

[1919]), p. 237.

[2] J. V. Stalin, ‘The October Revolution and the National

Question,’Works, volume 4 (Moscow: Foreign Languages Press, 1953

[1917]), pp. 169-70.

[3] ‘Appendix 1: Declaration of the Formation of the Union

of Soviet Socialist Republics.’ In J. V. Stalin, Works, volume 5 (Moscow:

Foreign Languages Press, 1953), p. 404.

[4] See

http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/russian/const/36cons04.html#chap10.

It also included the crucial article 124: ‘In order to ensure to citizens

freedom of conscience, the church in the U.S.S.R. is separated from the state,

and the school from the church. Freedom of religious worship and freedom of

antireligious propaganda is recognized for all citizens.’ This eventually led

to the rapprochement between the Orthodox Church and the Soviet government,

especially during and after the Second World War.

[6] Among many references, see V.I. Lenin, “Achievements and

Difficulties of the Soviet Government,” in Collected Works, vol. 29,

55-88 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1919 [1965]), pp. 68-74; V.I. Lenin, “From

the Destruction of the Old Social System to the Creation of the New,” in Collected

Works, vol. 30, 515-18 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1920 [1965]); V.I.

Lenin, “The Tax in Kind (The Significance of the New Policy and Its

Conditions),” in Collected Works, vol. 32, 329-65 (Moscow: Progress

Publishers, 1921 [1965]), p. 334-53; V.I. Lenin, “New Times and Old Mistakes in

a New Guise,” in Collected Works, vol. 33, 21-9 (Moscow: Progress

Publishers, 1921 [1966]).

[7] Deng, “There Is No Fundamental Contradiction Between

Socialism and a Market Economy,” in Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping,

vol. 3, 99-101 (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1985 [1993]), p. 100.

[9] Marx, “Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of

Political Economy,” in Marx: Later Political Writings, ed. Terrell

Carver (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 160.

[10] Mao, “On New Democracy (January 15),” in

Mao’s

Road to Power: Revolutionary Writings 1912-1949, ed. Stuart R. Schram, vol.

7, 330-69 (Armonk: M. E. Sharpe, 1940 [2005]), p. 335n.

[11] For instance, the “pivot to Asia” and effort to

“contain” China by the USA and its smaller allies are already in tatters as

China develops close ties with Russia, India, Africa and South America.

[12] See Domenico

Losurdo, Stalin: Storia e critica di una leggenda near (Rome:

Carocci editore, 2008).

[13] Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (New

York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1973 [1951]). In this case, the Left has

been deeply complicit in the Western agenda of the Cold War.

[14] Bruce Lincoln’s Passage through Armageddon: The

Russians in War and Revolution 1914-1918 (New York: Simon and

Schuster, 1986);Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War (New

York: Simon and Schuster, 1989).

[15] Theodore H. von Laue, Why Lenin? Why Stalin? A

Reappraisal of the Russian Revolution, 1900-1930 (London: Weidenfeld

and Nicolson, 1964); Oskar Anweiler, The Soviets: The Russian Worker,

Peasants, and Soldiers Councils, 1905-1921 (New York:

Pantheon, 1974 [1958]), 195-253; Marcel Liebman, Leninism Under Lenin (London:

Merlin, 1975 [1973]), 213-356; Tony Cliff, The Revolution Besieged:

Lenin 1917-1923(London: Bookmarks, 1987); Samuel Farber, Before

Stalinism: The Rise and Fall of Soviet Democracy (London: Verso,

1990); Moira Donald,Marxism and Revolution: Karl Kautsky and the Russian

Marxists, 1900-1924 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 221-46;

Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution (Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 1994), 156-72; Daniel Bensaïd, “Leap! Leaps! Leaps!,” in Lenin

Reloaded: Towards a Politics of Truth, ed. Sebastian Budgen, Stathis

Kouvelakis, and Slavoj Žižek, 148-63 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007),

156; Neil Harding, Lenin’s Political Thought (Chicago:

Haymarket, 2009), vol. 2, 283-328.

[16] Alexander Rabinowitch, The Bolsheviks in Power:

The First Year of Soviet Rule in Petrograd (Bloomington: Indiana

University Press, 2007).

[17] Cliff, The Revolution Besieged: Lenin 1917-1923.

[18] W. Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell, Towards a

New Socialism(Nottingham: Spokesman, 1993), 4-5.

[19] Domenico

Losurdo, Stalin: Storia e critica di una leggenda near.

__

The writer is a left-winger from Australia, based in the

industrial city of Newcastle. His main interest concerns the intersections of

Marxism and religion, having written a five-volume series called

The

Criticism of Heaven and Earth (Haymarket, 2009-13). He has recently

completed a long study on Lenin and religion. He frequently visits Asia and

teaches at Renmin University of China (Beijing). He blogs at

Stalinsmoustache.org

If publishing or re-posting this article kindly use the

entire piece, credit the writer and this website: Philosophers for

Change, philosophersforchange.org.

Thanks for your support.

__

De PHILOSOPHERS FOR CHANGE, 28/10/2014